In 2002, the Canadian Women’s National Hockey Team entered the Olympic Games in Salt Lake City in an unfamiliar position: as underdogs. They had not hit their stride as a team, their confidence had taken a hit, and emotions were at risk of boiling over. In eight head-to-head games against the Americans leading up to the Olympics, Canada had lost all eight. For many players, it was hard to avoid memories from four years earlier when the team had lost to the Americans in the gold medal game.

Jayna Hefford, who was playing in the first Games of her Hall of Fame career, recalls the point when the stress and emotion came to a head: “There was an intense conversation in the dressing room with the team. A lot of people had a lot to say about things we needed to do and how we were going to get better, and we realized that a lot of what was happening was the blame game.”

“We realized that a lot of what was happening was the blame game.”

Through a frank, players-only discussion the team was able to come together, but the conversation could have gone a number of different ways. It stayed on track because the team was prepared – mentally and emotionally – to have performance conversations under pressure and surface a number of issues the team needed to resolve. And that preparation turned out to be an important stepping stone to winning gold in Salt Lake City.

Training the bomb squad

Handled poorly, team communication under pressure can lead to combustion. And just like you wouldn’t get success as a bomb disposal technician going in without their toolkit, you won’t find success in communicating through tense situations if your team isn’t prepared. The advantage the women’s team had that allowed them to emerge from that conversation united was a deep awareness of their communication tendencies and systems to counteract the counterproductive ones. They had laid the foundation for performance conversations in good times so that they could happen and be productive when the difficulty hit.

In other words: they had a tool kit and they knew how to use it.

“The biggest opportunity for meaningful growth is often to increase self-awareness and strengthen their ability to communicate productively when under pressure.”

We’ve worked with hundreds of teams in elite sport and business, including the last four medal-winning Canadian women’s hockey teams. One of the things we’ve learned is that when teams are already operating at a high level, the biggest opportunity for meaningful growth is often to increase their self-awareness and strengthen their ability to communicate productively when under pressure. To support this, we’ve developed a process to help teams become more aware of their tendencies, develop systems and practice performance conversations anytime.

At the heart of this process is a tool called the TAIS – The Attentional and Interpersonal Styles inventory. The TAIS was developed for use by Navy SEALs and Olympic athletes, and we’ve found it to be an incredibly valuable tool for diagnosing communication challenges on all kinds of teams. When the pressure is on, when teams are in the midst of setbacks and failure, individuals will fall back on their default communication styles.

Five communication choices

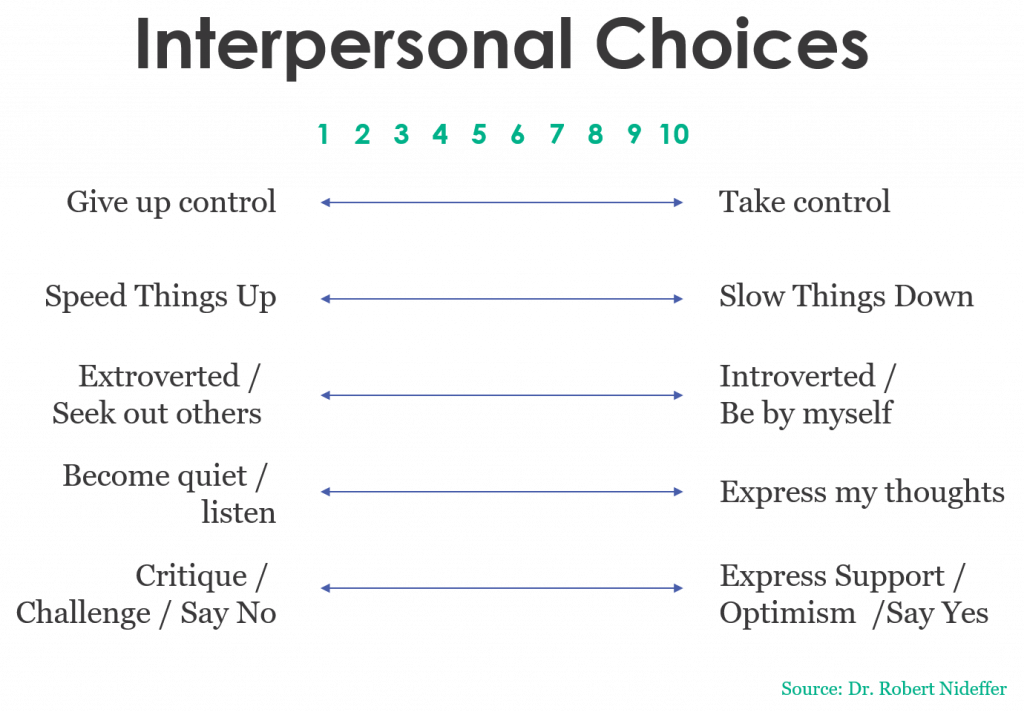

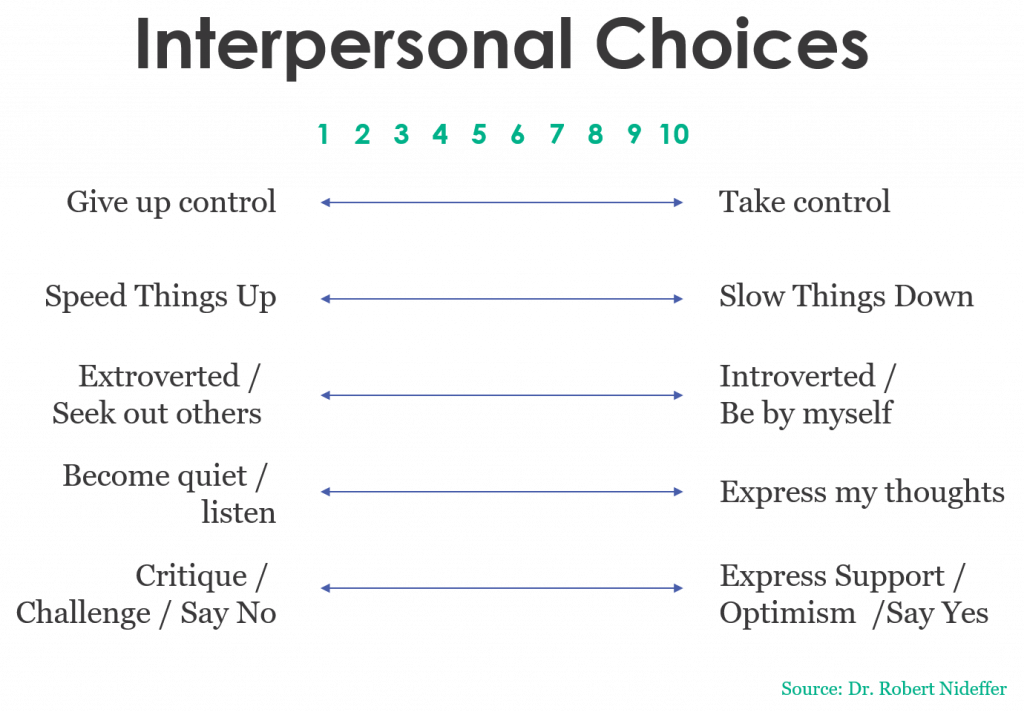

The author of the TAIS, Dr. Robert Nidefer, showed that people make five choices over and over in the course of a conversation. These choices are informed by their tendencies on five dimensions.

Give up/take control – are you more likely to try to take control, or cede control to someone else?

Speed up/slow down – are you more likely to force action or a decision, or encourage more thought and consideration?

Extroverted/introverted – are you going to seek out others, or try to solve the problem yourself?

Become quiet/express thoughts – are you going to become quiet and try to understand, or advocate for your position?

Critique/express support – will you say no and become more critical, or will you say yes and express support?

Cut the right wire

Every team will have members with different tendencies. Ultimately, it’s not the tendencies that matter; it’s the level of awareness team members have of their tendencies, and the systems they put in place to leverage their strengths and weaknesses in the heat of the moment. The highest performing teams we work with take three critical steps in preparing for productive communication under any circumstances.

Acknowledge the “I” in team

Great coaches know that the phrase “there is no I in team” is a myth. Every individual makes their own contribution – and without self-awareness, people can’t adjust. That’s why the first step in your team’s communication action plan is to encourage every individual to build self-awareness across these five choices. By knowing and understanding their default tendencies, team members can begin to recognize their behaviour and course-correct when necessary for the good of the team.

Connect to the “we” of the team

It’s advantageous to know your individual tendencies, and the value is multiplied when that information is shared with everyone on the team. When you raise the waterline of team awareness, everyone can work on the same communication system. Team members can see the intent behind the behaviors their teammates exhibit. The process can be incredibly difficult; Team Canada Captain Hayley Wickenheiser called sharing her profile with her team-mates, “the most stressful part of the 4-year [Olympic] quadrennial.”

Come together as a team

Armed with knowledge of self and others, teams can come together and translate self-awareness into action. When pressure hits, if everybody on the team has the tendency to get louder, express their thoughts and try to take control of the conversation, the team can make decisions in advance to decide who’s going to take control when issues arise. By having these conversations earlier, teams can build systems to fall back on when the pressure is turned up.

Preventing detonation

The next time you’re headed into a potentially high stakes conversations, use the five choices below to carry out a short 3-step preparation exercise:

1. Plot your default tendency on each of the five scales – given your past history, where are you most likely to fall?

2. Where would you ideally like to be as you head into this specific interaction?

3. What are the gaps between your ideal and default style? What actions will you take to ensure you are at your ideal?

Repurpose the fuel for growth

We’ve said before that negative emotion is volatile fuel. Improperly handled, it can lead to combustion. Used properly, it can lead to high performance.

Team communication must go beyond just staying cool during difficult times. Teams must use communication to understand and lean in to their negative emotions, uncover what the emotions are telling them, and frame it as an opportunity for growth. This is what happened with the women’s team in 2002. They prepared to have productive communication at all times, and used the tools they learned to find the opportunity for growth at a moment when it could have blown up. Jayna Hefford explains:

By understanding your individual communication style, sharing your tendencies with the team and proactively planning to address potential faults, your team can find its way through difficult times and not just safely diffuse difficult situations but find new strength and opportunity for higher performance in the process.